Indicine cattle or Bos indicus represents one of the two major subspecies of domestic cattle with a near global spread. Some of the earliest domestication evidence for this subspecies comes from Mehrgarh, an important neolithic archaeological site in present day Balochistan.

Recent scientific advances have allowed population geneticists to identify three distinct autosomal clusters - Indian, Chinese and African - for Bos indicus populations globally. Geneticists have also observed two major mtDNA (maternal lineage) strains, I1 (characteristic of the breeds that can be associated with a spread from the Indus Valley) and I2 (a more complex to understand strain, that may potentially be associated with the middle Gangetic plains).

Meanwhile, it's even more interesting on the paternal side as a recent study shows three different lineages for Bos indicus bulls - Y3a (a widespread and the most predominant lineage), Y3b (a lineage specific to West Africa) and Y3c (the paternal lineage typically found in South and Northeast India).

With the phylogenetic background discussed above in mind, this article will now try to shed some light on the timeline behind a near global spread of this important domesticated cattle subspecies. Two most important papers in this regard are McTavish et al (2013) and Verdugo et al (2019).

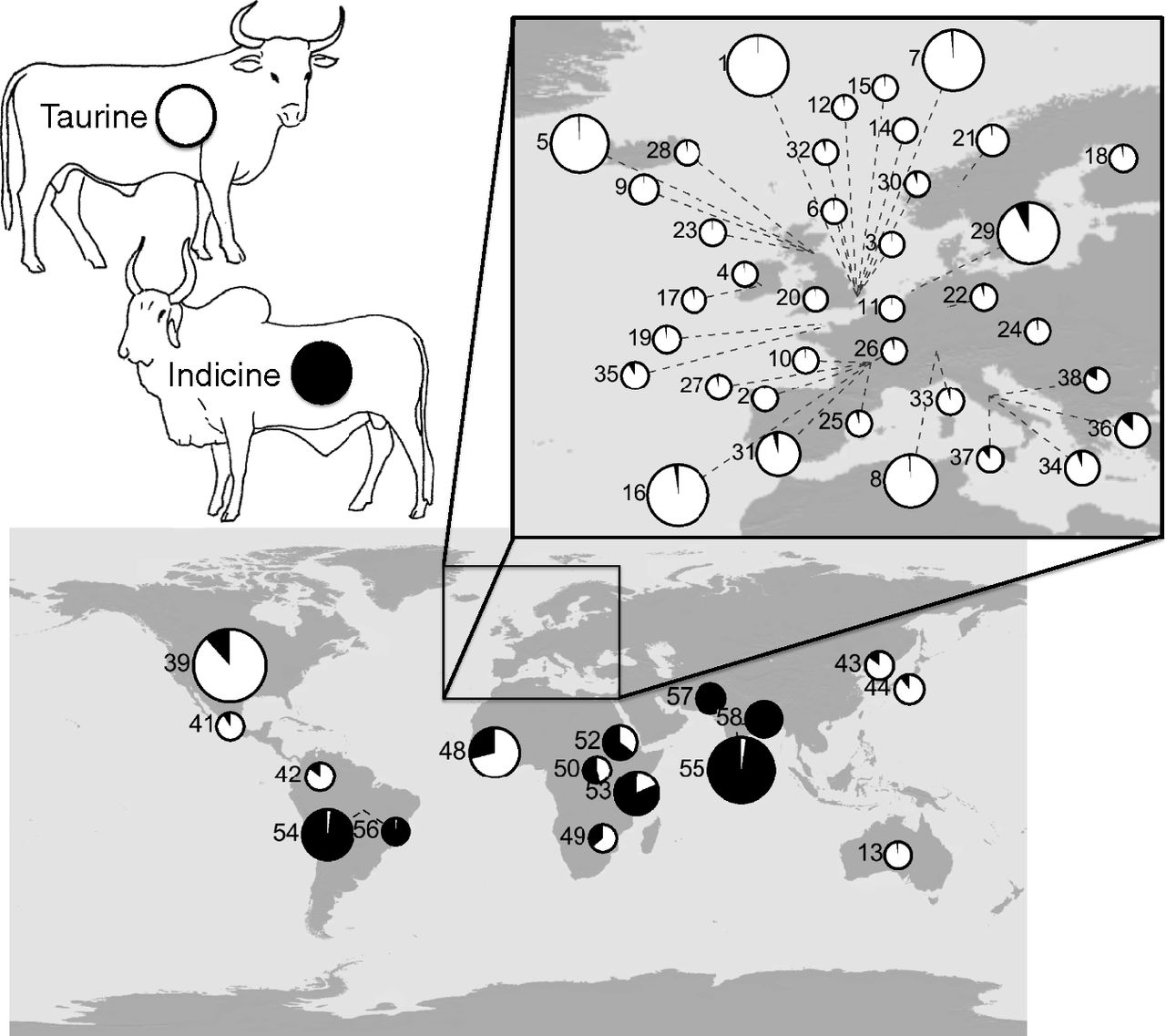

Using the image below from the McTavish et al paper, we can see that Bos indicus makes a considerable amount of contribution to the cattle breeds in Africa as well as in Southern and Eastern Europe.

Whilst it has been argued that a lot of the African Bos indicus spread happened with the Arab expansion after the emergence of Islam around the middle of the first millennium AD, there are some data points that hint at a much older presence of Indicine cattle in Africa.

The first piece of such evidence, from the field of population genetics, is the presence of a unique, area specific paternal lineage among the Zebu (Bos indicus) bulls in West Africa. This strain, haplotype Y3b, is not present anywhere in the modern Arabian world or further east in India and China. If this lineage had entered West Africa through the first millennium AD Arab expansion, we would have detected some presence (at least in traces) of this lineage in middle eastern Zebu bulls.

The next candidate movement in which this may have left the Indian subcontinent could have been the 4-4.5kya event described by Verdugo et al. Once again, if the bulls of this lineage went out in that expansion of Indian herders with their herds into the Anatolian plateau, then we would expect to see some traces of it left somewhere in the near east but this is not the case.

Given the current absence of this unique paternal ancestry in the middle east, the subcontinent and in the Near East sites known to have received a human mediated Bos indicus inflow during the Bronze Age, the presence of a unique, area specific Indicine cattle paternal lineage in West Africa appears to be the result of a pre-Bronze Age event and may very well represent a neolithic era movement out of the subcontinent.

While considering this possibility of an older movement of the Bos indicus out of the subcontinent, let's look at some of the time estimates given in a very recent 2021 paper by Senczuk et al. The authors of this paper determined that a split occurred within Taurine cattle leading to a separate identity of the present-day Podolian cattle breed in Italy around 6,500ybp (95% confidence interval ranging from 2,300 to 13,600 years ago); to reach these estimates they used an average cattle generation time of 2.5 years. Going further, they also give an estimate for the admixture timeline of Taurine and Indicine cattle; here, their results indicate an admixture date of 4,700ybp (95% confidence interval ranging from 1,650 to 10,800 years ago).

What we observe from the excellent data computed by Senczuk et al here is that using the 95% confidence interval range, there exists a possibility that the Taurine Indicine admixture in the Near East or the fertile crescent may be as old as the age of Taurine cattle domestication. Notwithstanding the current body of archaeological evidence (or the paucity of it) on the earliest date of domestication of the Bos indicus in the subcontinent, it is probable that the Near East cattle domestication event in Southwest Asia was the handiwork of the earliest Bos indicus herders from the Indus Valley.

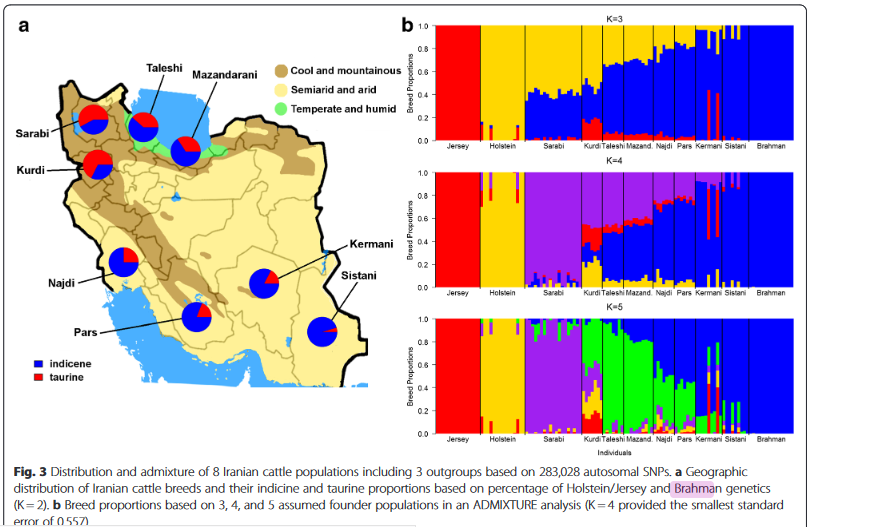

To examine the merit of this last assertion, we need to study the genetic makeup of the cattle breeds in Iran as the Iranian plateau serves as a natural corridor between the Indus Valley and the Zagros region. We'll use some of the analysis done in 2016 by Karimi et al.

This figure from Karimi et al shows a clear east west cline of Bos indicus introgression in Iranian cattle breeds. What is noteworthy here is that even the western most Iranian cattle breeds have a significant proportion of their genetic makeup attributable to Bos indicus while the eastern most breed (Sistani) is nearly all Bos indicus. This is a very important observation as it demonstrates that the most probable direction of movement of ancient (or, the earliest) cattle herders within Iran was east to west.